red eyes

a christmas trip!

Over Christmastime, my mom and I take a red eye to see our family in upstate New York. It saves a travel day and at least a hundred dollars if you fly at night, so we always do. It was the same this year. We left San Francisco International at 10 pm, and we landed sleepless in New York City the next morning. The terminals in JFK are windowless and gray, dotted with Dunkin Doughnuts and Hudson Newsstands. A giant Jack Daniels kiosk greeted us by baggage claim. It was weirdly difficult to find the exit.

But still, it felt like a gift. A whole day in the city. It wasn’t until the next morning that we would take the bus to our family upstate.

The day started off badly. I spilled my coffee on the E train into Manhattan. It spread out like a wide, spindly web across the floor, and the New Yorkers lifted their boots from the ground as the coffee neared them, glaring at me in hatred. I tried to make my face look both apologetic and blameless, like a Californian.

My mother and I dropped our bags in the West Village and walked to the Whitney Museum. We marveled at some purple colored prints that Ruth Asawa made with potatoes. In the afternoon, I met my best friend in Greenwich Village. We sat in the window of her favorite cafe off Washington Square Park, drinking coffees and talking about our hair. I complained about the cold. She crocheted me a hat. It was a great afternoon.

Everyone understands the city better than me: my mother, my friends, my sister. They’ve all lived there at some point, so they know all the subway routes and all the parks and all the best places to get frozen margaritas. I’ll follow them anywhere. Sometimes we’ll walk past a restaurant or a park that someone else took me to years ago, and then the city bursts with my memories of it. But if I start to slow down and really remember those things, I’ll have to stop in the street and then the New Yorkers will despise me. So I just keep following my family or my friends, letting all the red bricks blur into one, walking faster than I want to.

The next day, my mother and I caught a bus to Albany. The Port Authority Bus Terminal was packed. It is an unpleasant place, always stewing with impatience and dread. But I do like the long bus ride. I like watching the world flatten as the bus leaves Manhattan. The skyscrapers sink into strip malls, and the houses begin to line up next to each other instead of on top of each other. The bus drivers always seem to question why anyone would be on a bus to Albany.

“Last chance to get off if you’re NAHT going to Albany,” they shout into the intercom. “It’s damn cold up there, and you’re NAHT going to be happy if this is the wrong bus.”

Fortunately, everyone onboard fully intended to go to Albany. But no one seemed very happy about it.

Three hours later, my dad and my older sister picked us up at the Albany bus terminal. The sky was pitch black and the air was freezing, biting through my coat. My sister rolled down the window and stuck her tongue out as their car pulled up. I hadn't seen her since June.

“Hey,” she said, hitting my shoulder.

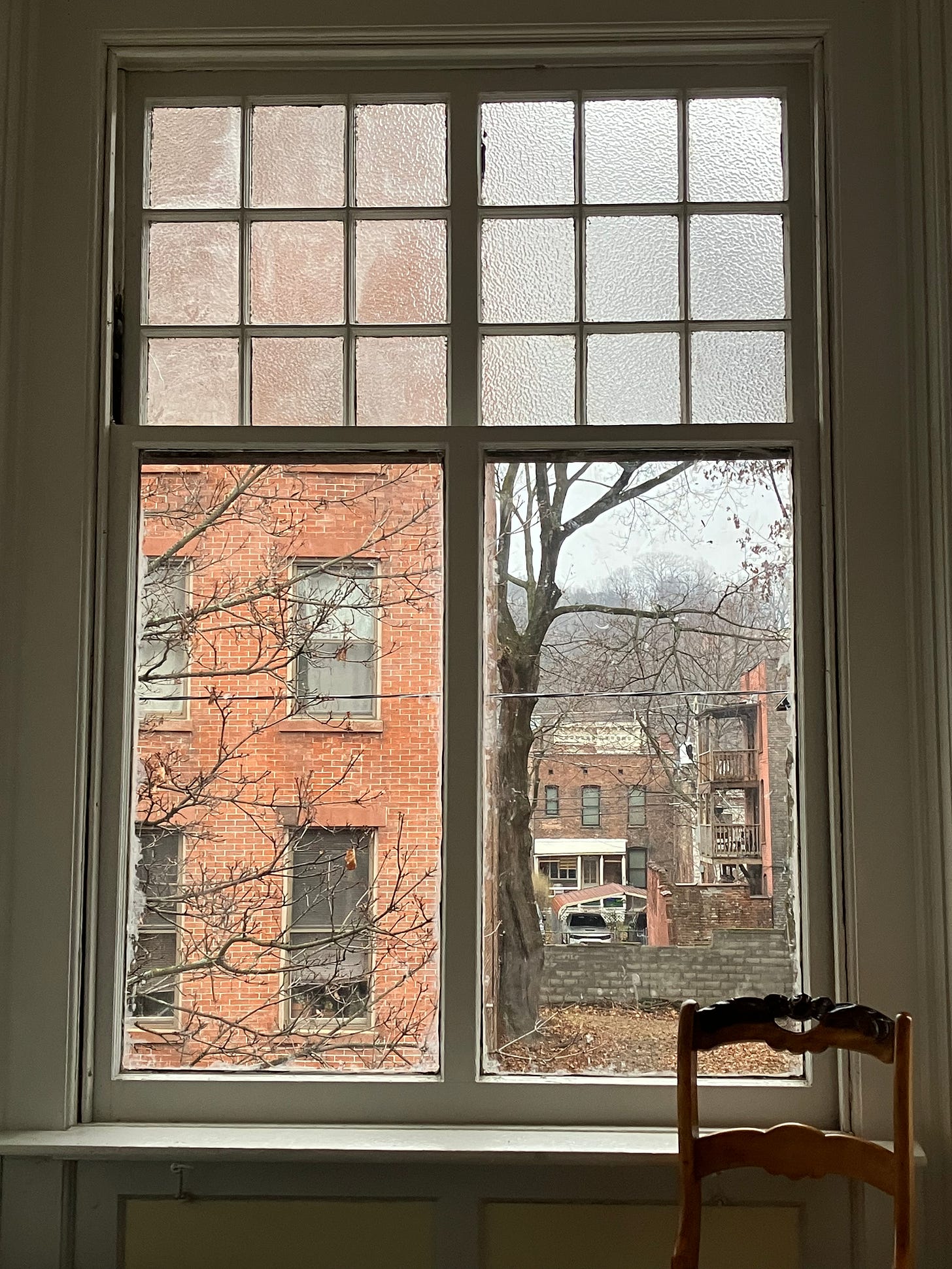

We drove across the Hudson River to my parent’s hometown, Troy. It’s a tiny city. but it has so many brownstones you could almost believe you were in Brooklyn. Knotted tree branches dabble the sky, like aimless pen marks. Nowadays, you can get most anything in Troy: oysters, wine, white chocolate peppermint mochas. I am often reminded that it was not like this when my parents were growing up here in the seventies. Troy became a city during the Industrial Revolution, but by the mid 20th century, all its factories and smokestacks had been abandoned. Only the grocers and the mailmen and the wives remained. So they kept living, because there was nothing else to do. The mail kept coming, and the groceries kept getting delivered, and the winter winds tumbled through the brownstones, like seawater through an empty shell. The local government made bad decisions, again and again. They tore down half the historic downtown in the eighties, with some vague plan to ‘modernize’ the city. Then they built half a mall and ran out of money for the project, so they gave up. Troy went on and on, like some stupid grudge, struggling forwards against its will, begging for its story to end. The surviving brownstones started to crumble. Then, a few years ago, some urban hipsters discovered Troy and made it their own. It’s on its second life.

That night, we ate dinner at a wood-fired pizza restaurant next to the music hall. My sister told us about a new character in town: a businessman named Vick Christopher, who has economic ambitions not unlike that of Mr. Potter in It’s A Wonderful Life. He owns most of the new cafes and restaurants downtown–the kinds of places where you can get zinfandels and zucchini pickles. He plans to own more. My sister is boycotting his businesses.

Troy is surrounded by coiled highways and thick forests. We don’t drive on the highways much–they are windy and confusing. Giant orange warning signs flash at drivers from the side of the road:

“IF YOU DRIVE DRUNK, YULE BE SORRY!”

The other day, I had a headache in the car and thought I hallucinated this sign:

“YOU’RE OUT OF YOUR MIND . . . “

Then it flashed orange and the letters rearranged:

“IF YOU DRIVE HIGH!”

No one in my family likes these omniscient signs, so we always take the longer routes through the countryside. The sky is white and the trees are black, and they clasp each other like cold hands. The roads are lined with aging cemeteries. The faded headstones spill over the hillsides, and thin, tilted pillars topped with angels beckon towards nothing. My dad drives past these places quickly. But he slows down on the roads that line the Poestenkill Creek, peering out the window to look at the rapids. When he was twelve, he explored these shores too much and accidentally discovered a nudist beach.

“Really?” I exclaimed when he told me this.

“Yeah,” he said, “Bare Ass Beach.”

My sister, too, prefers these roads to the more convenient ones. She moved here two years ago and learned the routes from my family. She can point out the graveyard that our great-grandfather used to work in, and the bakery that my other great-grandfather used to own. The roads are an extension of herself. They are like aging hands and fingers, swollen with the past. I ask her why she doesn’t live in New York City.

”They have nothing like this,” she says.

She likes to drive around wearing my grandma’s old fur coats and a pair of cowboy boots she bought on Etsy. ”Real snakeskin,” she tells me. It's quite the picture: Lucy decked out in aviator sunglasses and bolo ties, reciting stories about my grandparents and screaming rock ballads in my great-aunt’s old mini cooper. There’s a rubber duckie taped to the dashboard.

Usually, Lucy takes these winding roads to band rehearsal. She joined a country rock group called the Brule County Bad Boys in the fall. They seem to be doing quite well for themselves. They’re playing at a local bar during the midnight countdown on New Year’s Eve, and they played at a club in New York City in November. I have begun to hear this exchange often between my parents:

“Where is Lucy?”

“She’s with the Bad Boys.”

Apparently the Bad Boys came to the flat in early December and made Christmas ornaments and holiday cookies. She is with them now, tie-dying their new merch and complaining about Vick Cristopher.

When I was in high school, I couldn’t imagine why anyone would want to live here. Why would anyone choose to live in a colorless place, in a place lined with faded reminders of the dead? But we don’t always get to pick the places we love. My sister loves it, deeply. So I’ll be here for a little while, in the passenger seat of her mini cooper, listening to stories and trying to avoid whatever might remain of Bare Ass Beach.